![]()

Milan Kundera observes somewhere that the novel does not write a society’s history. Its overwhelming concern is, rather, with the existential condition of the individual. Philosophical discourse is not part of its provenance, though its characters may engage philosophy where the latter is not the object of novelistic intention but only an element of its strategy, to reveal tellingly some aspect of the character’s persona.

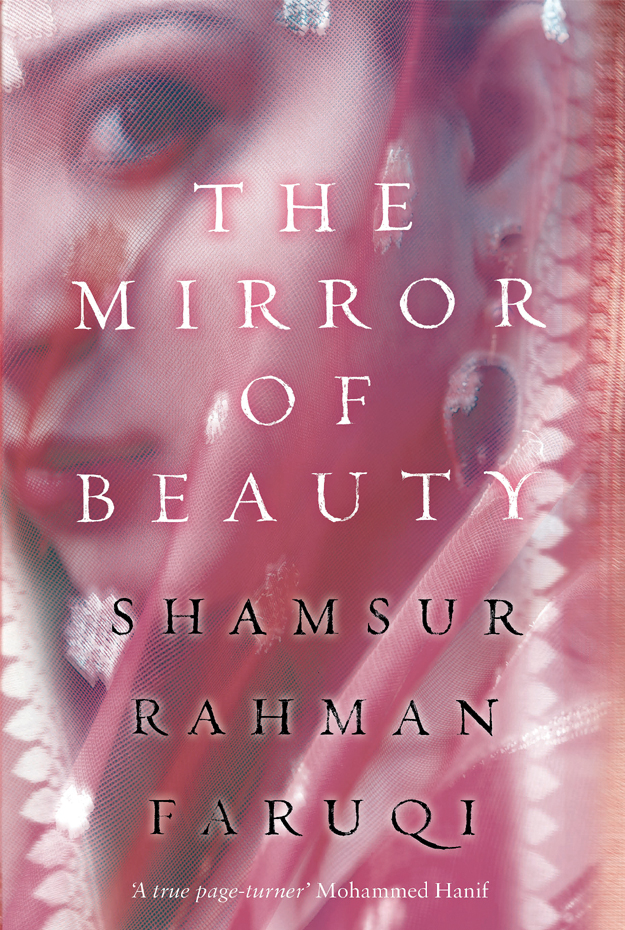

In his masterwork, The Mirror of Beauty (Hamish Hamilton, 2013; 958 pages), Shamsur Rahman Faruqi seems to have found a happy medium. It is a novel as much about a woman — a stunning beauty of elegant grace, infinite dignity and gravitas — as about Indo-Muslim culture in its heyday and during its precipitous decline, mostly at the hands of the British in 19th-century India, but partly also because of the sapped energies of the latter day Mughals who failed to rise to the demands of statecraft with shrewdness, creativity, and grit. But perhaps the overarching impulse behind this work’s creation springs from the author’s tender regard for a way of life whose memory is fast receding from our collective memory — to preserve before time has annulled what was once a living, scintillating reality, or, at least, our romanticised vision of that reality.

![]()

Faruqi does not, however, use his protagonist as a living museum for the display of cultural artefacts, divested of personality, volition, and selfhood. His intimate knowledge of a bygone era, its people, their manners and language, compounded by an uncannily intuitive sense of the nuances and intricacies of the poetics of good fiction, enables him to interweave the quintessential qualities of both with such deftness and surety of touch that the two melt, almost as a dialectical necessity, into a breathtaking intimacy. It is the culture that makes Wazir Khanam who she is, and it is the mirror of her being in which the entire elegance of that culture, its decorum, its insatiable love of the literary arts, miniature painting, music, a myriad of crafts, even maladies and their indigenous as well as Greco-Arab cures, is reflected in a rainbow of warm, dazzling colours. The delightful ambiguity of “beauty” in the title further reinforces the author’s twin concern, as the beauty of the protagonist and the culture meld so seamlessly it is impossible to think of them as separate entities, or to discern where reality eases into illusion.

![]()

But it is a beauty as much illusory as tangibly real. Illusory in the form of the non-existent Bani Thani (“The Bedecked One”) who dominates the first 150 pages of the novel, and every bit as sensually real as the ravishing Wazir Khanam of the remaining 850. Either way, its seductions prove fatal in the end. Even as it generates the desire for heaven or for earth, it destroys by its lethal effects on men.

Central Asian culture, transplanted to India by the Mughals with an ecumenical incorporation of native Indian customs and conventions, is enacted through Wazir Khanam and a fairly extensive cast of characters, some from the lower classes and in subservient roles, but most drawn from the upper crust — indeed some of them historical personages — and in commanding positions. And all this in the midst of the irritating presence of the foreign intruder: the Company Bahadur.

The English, literally in awe of the majesty of Indo-Muslim culture before the 1800s, had acquired, as William Dalrymple notes in The White Mughals, all the hubris and arrogance of an upstart with the advent of Wellesley on the horizon of India in 1798 as governor-general.

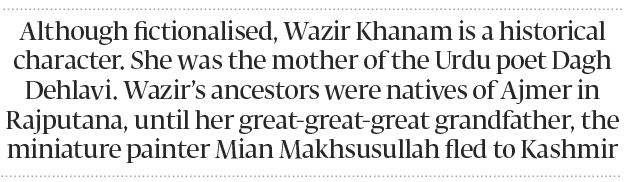

Although fictionalised, Wazir Khanam is a historical character. She was the mother of the Urdu poet Dagh Dehlavi. Born sometime in early 19th-century Delhi, Wazir’s ancestors were natives of the Hindal Purwah village some twenty miles from Kishangarh in the province of Ajmer in Rajputana, until her great-great-great grandfather, the miniature painter Mian Makhsusullah fled to Kashmir. He had painted the image of an imaginary Bani Thani. On an unscheduled visit to his estate, Maharval Gajendrapati Singh saw the iconic image hanging in an alcove of Mian Makhsusullah’s hut. Its lifelike resemblance to his own younger daughter Man Mohini so enraged him that he suspected some promiscuous goings-on in the back of the portrait. He had Mohini brought in a palanquin, accused the innocent girl of dishonouring him, and slit her throat, giving the residents until the next morning to vacate the village. Still later, Mian’s two grandsons, the twins Daud and Yaqub, moved to Farrukhabad and Delhi, with a brief stopover in their ancestral Rajputana, where they lost their hearts to two ravishingly beautiful orphan sisters and married them.

![]()

But who is this enigmatic Bani Thani, and was Mian Makhsusullah’s some morbid fixation?

By the time Mian arrives in Kashmir he is firmly resolved never to paint again. He learns, instead, the art of producing talim-ie, creation of exceptionally intricate designs for carpet weaving. However, the imaginary Bani Thani is so enmeshed in his being that he paints her yet again, this time on ivory, and hangs it in an alcove in his atelier. He would gaze at it many times during the day and, as often, during nightlong vigils. He lives, but just. His soul is on fire, desperately seeking an ideal well nigh unattainable in this life. The day his son is born, he places the infant in the arms of his brother-in-law and leaves the house never to return. He is found reclining against a mighty oak, covered in his blanket — dead, his hand curled over the piece of ivory. The two are laid to rest in a single grave.

The strikingly beautiful and mysterious Bani Thani represents a Platonic ideal, not some flesh-and-blood woman. “Some people also described her as ‘The Radha of Kishangarh’, meaning the beloved of God Krishna.”

The reference to Radha, “the beloved of God Krishna,” and the disquietude in Mian Makhsusullah’s soul, as much as his absorption in something beyond human contingency, represent, what Shelley eloquently calls “The desire of the moth for the star, / Of the night for the morrow, / The devotion of something afar / From the sphere of our sorrow.” In other words, the painful realisation of the yawning gulf between the phenomenal and the transcendent eternal, and the impatient desire to be gathered up in it until all consciousness of personal ego is extinguished — a notion common enough in the Sufi metaphysics of Wahdat al-Wujud. Makhsusullah (Appropriated by God) may not have been a Sufi, but his every movement belies unmistakable sufic strains: his detachment, his otherworldliness. Bani Thani to him was a symbol of something lacking, but necessary, in human existence, something sublime and of an infinitely higher order that existed beyond time, and drew him inexorably to itself. He may not have been able to articulate with the clear vision of a Sufi, still his Bani Thani was the mimesis of the cosmic spirit in an imagined earthly medium.

![]()

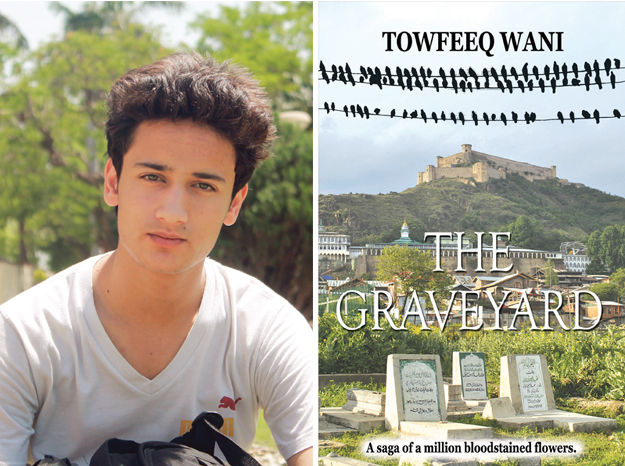

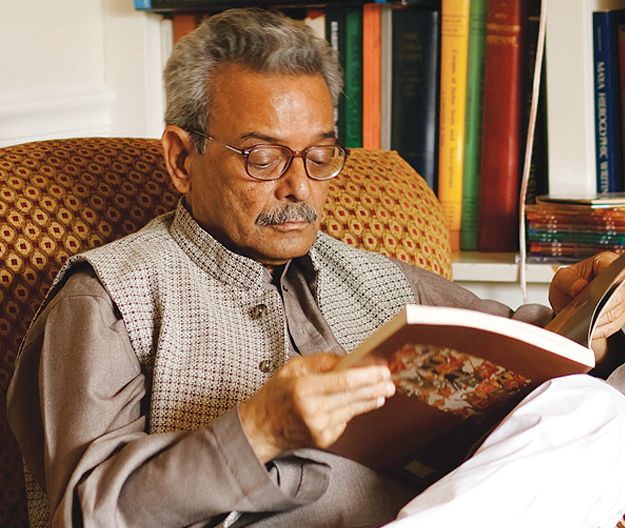

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi worked as a civil servant in the postal department until his retirement. He is a poet, critic, and literary theorist acclaimed for this three-volume critical work on the Urdu dastan.

Wazir’s character dominates the novelistic space from Book 3. She comes through as an individual minutely conscious of her unassailable erotic powers over men. But she knows how to restrain those powers from riding roughshod over her drooling admirers, schooled as she is in the courtesies and mores of her culture, and deferential to a fault to its requirements and limits. Lively, self-willed, unwilling to submit to domesticity, full of wit and subtle humour, with a passion for life and aware of the demands of her flesh, she never oversteps those limits yet manages, amazingly, to preserve her individuality.

Mistress of three men (Englishman Marston Blake in the employ of the Company Bahadur; Nawab Shamsuddin Ahmad Khan, a close relative of the poet Ghalib; and Agha Mirza Turab Ali), hoping someday to rise to the status of wife, she is singularly unlucky as the lives of all three are snuffed out prematurely. Blake meets his end in Jaipur at the hands of an overexcited mob that suspected the Company of interfering in the business of the Maharaja’s succession; the Mirza is done in by thugs; while the public hanging of the Nawab owes in no small measure to the rivalry and ultimate humiliation of the Resident to the State of the Company Bahadur, Nawab William Fraser Sahib, who had lost the affections of Wazir to the handsome Nawab. (Not content with his burgeoning seraglio of half a dozen desi bibis and numerous boy-lovers, Fraser wanted to add Wazir to his sprawling harem as well.) Her fourth wooer, none other than the Mughal prince and heir apparent Mirza Fathul Mulk Bahadur, who finally bestows on her the much longed for and much delayed dignity of becoming a legally wedded wife, dies suddenly in 1856, a year before the sun was to set irrevocably on the Mughal Empire, or whatever was left of its nominal authority amidst the steadily encroaching power of the English.

![]()

Wazir goes through her tragic vicissitudes with exceptional grit, stoicism, and grace. The deaths of the four men in her life, whom she loved in her own way, are not the only wounds life has given her. Practically disowned by her religiously devout father and eldest sister, who could not put up with what they assumed to be her unforgivably unorthodox ways, she also had to suffer the haughtiness, the sleazy machinations, the petty-mindedness and jealousy of the relatives of her four lovers. Not only is she divested of material assets after their deaths, even her two children with Blake are practically snatched away from her lap by Blake’s cousins, the Tyndales.

By the time the novel has moved to Wazir Khanam, the spiritual purity and considerably less materialistic aura of the traditional culture has undergone a palpable change. The affinity of Wazir and Bani Thani is not in the physical realm but in a notion of beauty — bewitching enough to put men beside themselves.

Something of an epic in its magnificent expansiveness, the Mirror defies any attempt even to enumerate its tantalising wealth, much less to adequately discuss it in a few hundred words, which would be like the attempt “To see a world in a grain of sand” and “eternity in an hour.” The whole way of life of 18th- and 19-th century India is gathered in the novel’s encyclopaedic sweep. One can literally assemble several inventories of manners, ceremonies, festivals, fabrics, jewelry, arts and crafts, arms and weaponry, you name it. The description of Wazir’s attire at her first visit to Nawab Shamsuddin alone is spread over four pages, and that of his palatial residence in Daryaganj takes up over five.

Some individuals defy our notions of human possibility and limit. Faruqi is one such individual. A civil servant in the postal department until his retirement, he accomplished in letters what few are able to in educational institutions and literary academies. A poet, a critic, a theorist of literature, a fan and translator of detective novels, a polymath, with a profound knowledge of music and painting — the list of his achievements is endless.

As if his studies of Ghalib and Mir, his incisive comments about the nature of fiction, his insightful forays into lexicography and prosody, and, lately, his three-volume critical work on the Urdu dastan, a stunning contribution to world literature, were not enough to leave ordinary mortals breathless over his vast erudition and creativity, he has achieved in a single novel what writers toil a lifetime to achieve, but few ever do: the brilliant portrait of a vanished time.

Faruqi came to fiction later in his career with the publication of half a dozen short stories, later collected in Savar aur Doosray Afsane. While readers were still reeling from the stunning beauty of these stories, a treasure of cultural riches broke upon their senses with a crashing force — his gargantuan novel Ka’i Chand the Sar-e Asman (The Mirror of Beauty in its English reincarnation).

A reworking in English of the Urdu original, the Mirror rarely drifts away from the main events of the original. And Faruqi alone could have accomplished this formidable feat. The characters of a bygone age, their every breath and movement steeped in the unmistakable ambience of a self-sufficient but, ultimately, doomed culture, with its penchant for high-living, pleasure, allusion and poetry, required an idiom commensurate with their times and cultural personality. Faruqi’s stylised English — notwithstanding its few infelicitous contemporary “hey” and “girlie” and “you son of a gun” — gives the novel its razor-sharp edge of authenticity.

India should be rightly proud that two of the greatest living Urdu writers, both recipients of the Sarasvati Samman — Faruqi and Naiyer Masud, an academic, research scholar and a short-story writer — make their home in its bosom. And Penguin, equally, should be congratulated for publishing them both in the same year (Masud’s The Occult, Seemiya in its original Urdu, will appear later this year).

The Mirror of beauty is available at Liberty Books for Rs1,271 after 15% discount.

A shorter version of this piece first appeared in Mint Lounge (ww.livemint.com)

Dr Muhammad Umar Memon is Professor Emeritus of Urdu Literature and Islamic Studies. He has been associated with the University of Wisconsin Madison since 1970.He is a scholar, translator, poet, Urdu short story writer, and the editor of The Annual of Urdu Studies.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, August 11th, 2013.

Like Express Tribune Magazine on Facebook, follow @ETribuneMag on Twitter to stay informed and join the conversation.